This dialogue is part of the series of dialogues with creators supported by IN TRANSIT and internationally active artists and other expressers. The other day, the artist collective OLTA staged a performance of its new play Eternal Labor at the international arts festival Aichi Triennale 2025. The dialogue participants from OLTA are Jang-Chi, its director, and Meguninja, who wrote the script and also appeared in the play as an actor. The two joined in discussion with River Lin, who was born in Taiwan and is currently active as an artist and curator based in both Paris and Taiwan. Lin, who has seen several OLTA works, interviewed Jang-Chi and Meguninja after watching Eternal Labor, OLTA’s latest play.

Aichi Triennale 2025

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Clockwise, beginning from the left side of the back row: OLTA’s Jang-Chi, River Lin, and OLTA’s MeguNinja.

* How do you express invisible things such as “ideology” and “labor” with the body?

River Lin (hereinafter referred to as “Lin”)

The moment I entered the theatre space, which had been transformed into a video game playground for an exhibition, I was amazed by how audience members activated video-game installations and characterized the constructed site. The playfulness of the space soon gave way to many dark rabbit roles as the play unfolded. Throughout the work, a screen shows a real-time clock counting up from the history of mining.

The concern of mining framed the origin of the work and to me recalled to your previous work, The Japanese Ideology, performed in 2023 at the end of the pandemic. The attitude of rethinking and delving into the issues facing Japan and its society, which are also themes of the play, struck me as a continuation of this play. From The Japanese Ideology, I would like to know what has stayed and what has evolved that led to Eternal Labor.

Jang-Chi

In my activities for OLTA, I have continually grappled with the questions of the kind of influence that historical events in the background of Japan’s modernization have exerted on the present, and how that influence can be expressed on the stage. As for The Japanese Ideology, many people have left behind books on the subject so far. I consulted that by Jun Tosaka titled Nippon ideorogi ron (The Japanese Ideology, published by Iwanami Bunko), for example, and have been interested in statements by emperors recorded in official documents and popular songs of their times. The script of The Japanese Ideology contains words apparently linked to ideology from such past statements, paralleled by many quotations and references in Meguninja’s text.

Meguninja

One of OLTA’s plays is Hyper Popular Art Stand Play (2020). For it, all members of OLTA researched unconscious motions and behavior latent in everyday life. The play applied a methodology of having all members narrate the script. In writing it, I did not view the individual characters appearing in the play as fixed, but instead drew them with a conscious awareness of the anonymity and namelessness of life in a city. After I became mainly the playwright (beginning with Land of the Living, 2021), I focused on everyday conversation while carrying on the troupe’s basic style.

For The Japanese Ideology, I collected pieces of ideology that casually crop up in everyday speech and conversation, and focused on what consequently came into view. I think it was a provocative work that prompted viewers to notice how they felt when faced with such words, quotations from official documents and the statements made by emperors that are shared throughout Japan.

Jang-Chi

For Eternal Labor, I turned my attention to resources as viewed from the perspective of coal mining, and pondered the question of how to perceive capitalism and democracy. This is a big point of difference from The Japanese Ideology. Although the fundamental thinking in the aspect of direction remains unchanged, we created a play that explores how to get bodies to rise up from things, equipment, and environments, and capture them as vehicles and media for communication, in OLTA style.

In The Japanese Ideology, I regarded ideology and average as interlinked concepts, and bore “leveling” (averaging) in mind in my direction of the play. The stage is mainly a level floor. In the case of Eternal Labor, we prepared the play while mulling over ways of expressing energy from the standpoints of capital and resources. This time, we wanted to shed more light on the “burden” on the vehicle and movement. There are several slopes in the space, and the actors often go up and down them. Whatever the work, I am conscious of the conceptually upper and lower structures. In the case of Eternal Labor, however, I make these structures visible by scattering fragmentary scenes on slopes and other stage props as well as within stage space.

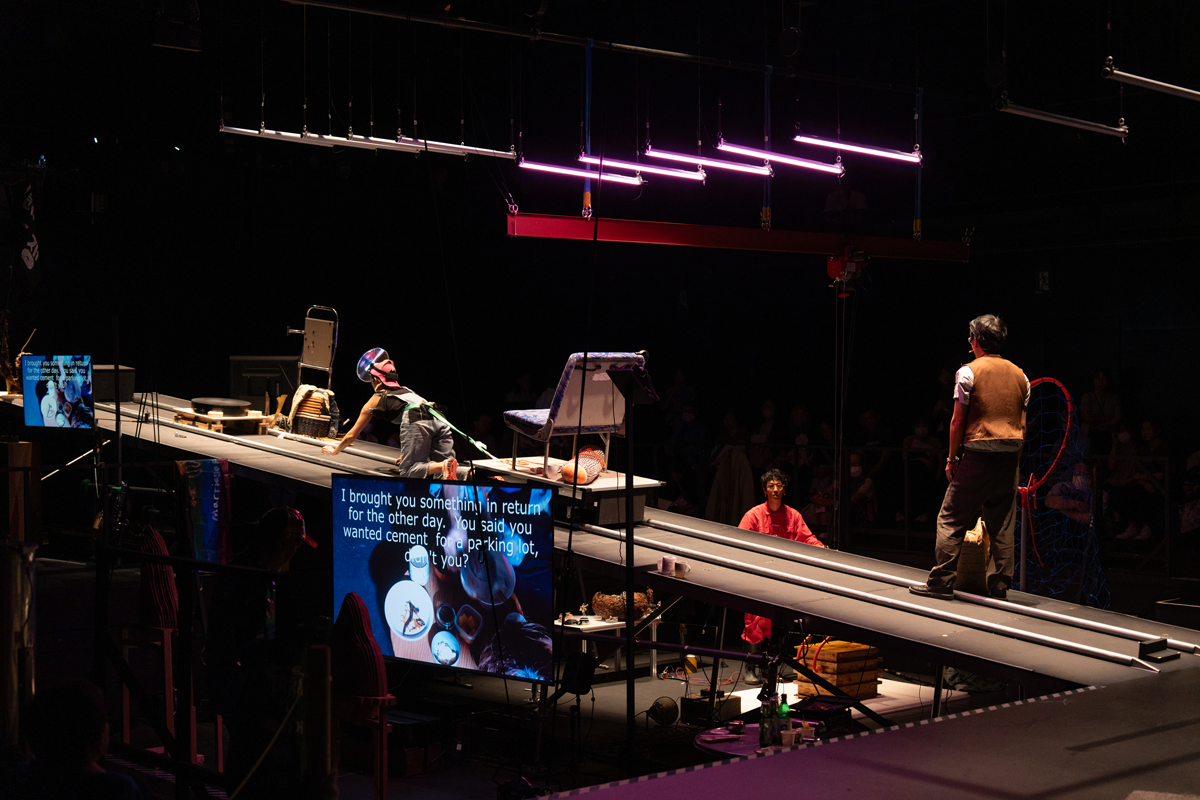

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

* The history of colonial oppression and ties between Japan and Korea as appearing in the movements and behavior of characters

Lin

From watching the play, I got the impression that it was providing a representation of, or mode of being for, the body in everyday life. In particular, in Eternal Labor, the characters have a background in the form of birthplace and title. People of diverse classes in terms of the power structure also appear on the stage, but they are portrayed as having one thing in common: they all have fallen by the wayside in today’s society, have been marginalized, or are unwelcome or unappreciated—that was my impression. My next question has two parts. First, when such people appear on the stage in the play, what body language do they use, what movements and gestures do they make, in their expression?

The second has to do with social problems from history that are taken up in the play. For example, the coal mine, the history of Japan’s colonial oppression, and especially the relations between Japan and Korea. In my understanding, the problems are ongoing. In this work, what kind of action do you want to cause by bringing them up? I would like to learn about your aims.

Jang-Chi

The gist of the first question is the kind of body language I am trying to elicit. In response, I will comment on my aims in directing, that is, how I want the actors to be on the stage. One is a “mechanized body.” The model is an employee of a game center wearing a suit of armor. It could also be likened to a robot in a restaurant or shop that can only say a few key words such as “welcome” and “thank you.” In addition, the role of the video creator is to have the actor attach a 3D program display on their faces. She edits the video footage, but on the displays flows a stream of words expressing anxiety about being compelled to do jobs she does not want to do.

We are also making various attempts at expressing the everyday burden on stage. For example, putting something into the body and then expelling it. There are many scenes of eating, and I additionally made a point of showing menstrual blood and urine as things that are physiologically discharged from the body. The actor wearing a suit of armor stands atop the slope holding a stainless-steel ruler about two meters long. He proceeds to place it on his head while standing still and then to take one end in hand and swing it while walking. I added this scene with the relationship between tension and utterance in measures in mind. There is another scene in which a girl of high-school age named Miki engages in dialogue with ChatGPT. I tried to show this dialogue by having a close-up of her eyes, which move as she engages in it. This too was an attempt to see what I could express by movement of a part of the body.

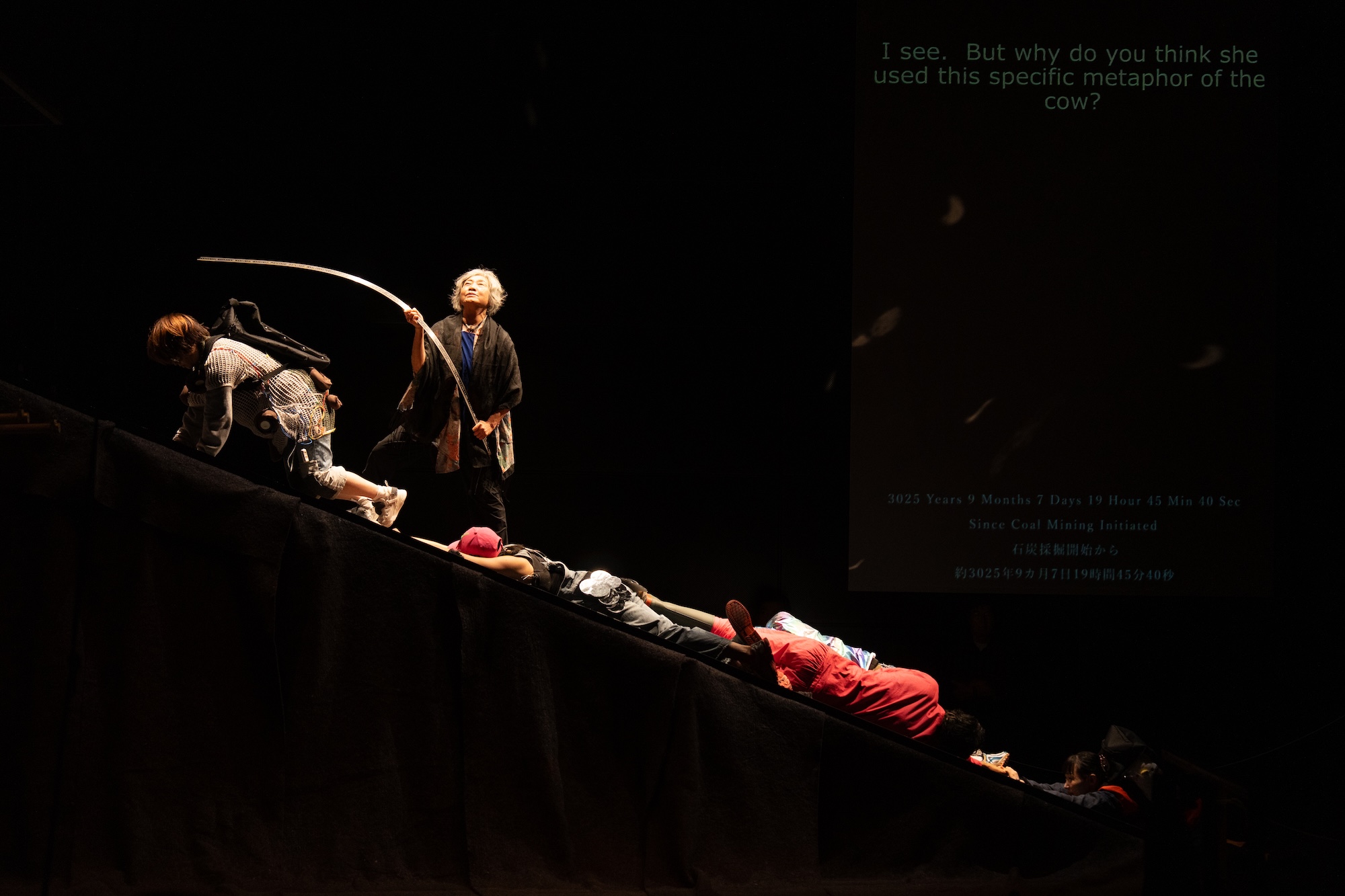

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

Meguninja

I initially thought of “women” and “labor” as the theme, which would have an extremely wide scope. I also realized that women could not all be lumped together in discussion on some aspects. I referenced The Third Sex, a book by Kazue Morisaki, which consists of the correspondence between two women, each writing from their own perspectives. Even on the subject of having children, they differ: one cannot have children because of a disease, and the other has children. I figured that to think about women and labor was to think about “women’s bodies.” In connection with labor, I first visited coal mines in the cities of Kita-Kyushu and Fukuoka in Fukuoka Prefecture, and then one in Korea. I did this fieldwork while constantly considering the connection with the present.

In my script, I portrayed diverse outlooks on labor through the characters; one says she cannot do any physical work, another wants to work with as little exertion as possible, and yet another is always looking for ways to make money. I describe how labor occupies the largest single part of human life. A little earlier, I mentioned the question of whether or not women have children. I sprinkled such dichotomous elements throughout the text. In our lives, there are actually many moments when we are confronted with a dichotomy and must make a choice. In not a few cases, the choice is actually made less by us and more by the circumstances and environment. The most obvious example may be the choice of whether or not to have children, but my point is that there is an extremely strong connection between gender and choices in life. In this work, I guess I wanted to examine how such conflicts are linked with the way people live.

Lin

To talk a little more about physicality, I would especially like to know how the laboring bodies get up on the stage. It looked to me that there were several types of bodies on the stage. First came the part-timer at the game center, the convenience store employee, and two single mothers. They were followed by housecleaning labor, beekeeping, and the job of a cram-school teacher. Besides these types, there were also abstract expressions of labor that seemed to crawl out from under the ground. There exists something like an extension and amplitude of labor, per se. The play seemed to offer examples of the kinds of labor that are continuous with history and present in contemporary society.

The characters I am especially interested in are the two high-school girls, and the influencer and video creator. These two pairs seemed to most radiate a special presence in the play. While this may be a little too heavy, what they share in common is an extraordinary feeling of despair. They do not have a very strong motivation to live, and are always asking themselves why they have to go on living. The influencer and video creator produce content out of their desire for money and approval. In a scene in the first half of the play, they shoot footage of themselves getting rid of bees.

At that time, there was a line that went something like “this one will be a hit.” To me, it suggested that they had not yet had a stream go viral, and wanted to become famous. Similarly, the conversation between the two high school girls was very dark and showed no signs of hope. In it, one felt despair, but at the same time, that the two were depending on each other. In the play, these two pairs function as highly emotional beings, and this may be because they reflect the current situation in society. They say that they are at the bottom of the social scale and cannot find an exit. One character that struck me as mysterious was Aso. He seems to be a kind person, but is not on stage the whole time and appears somewhat distant from the other characters. His existence, too, stayed on my mind.

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

Meguninja

As their names suggest, one of the two high-school girls is Japanese, and the other, Korean. They are symbols of a relationship of offense and victimization. Although they both study at a regular school, they also study at an after-school cram school, and are tired out every day. Moreover, the high school and cram school are places where the good and poor students are clear to all. This is how cracks begin to open in relationships. The two are also forced to do labor in a closed space, and cannot find any hope. Aso is the role of an authority in this district. He is modeled on the plutocrat based in Fukuoka that started out by managing coal mines. Because he is a capitalist, he can appear and disappear at any time. He may even help people at times, but I had him appear as a symbol of a person who is capable of using people as he likes.

Lin

I was struck by the wide range of generations in the audience. I imagine the generations above ours watched the play as one based on the history of Japanese colonization and oppression, but those younger than they—for example, members of Generation Z like Miki and Ji-Eun—with what interest do you think they watched the play?

Jang-Chi

I think the performance itself was seen by a fairly wide range of age groups. But I have not spoken much with members of Generation Z, and would really like to hear their opinion. I imagine that Japan and Korea differ in respect of the orientation of education in history, and am interested in how they saw the play.

Lin

This play unfolds not only in the form of a performance but also in that of an installation whose display area was like a game center. In addition, the influencer participates in a VR demonstration at the close, and I was amazed at this ending. The way in which a play ends seems like a response from the playwright at that point in time. Caught in an impasse and unable to find a way out, the characters apparently head for the world of VR. My question is: when you incorporated digital culture, avatars, and other technology into the play, how did you want these elements to function? Please also tell me about the connection between technology and this work.

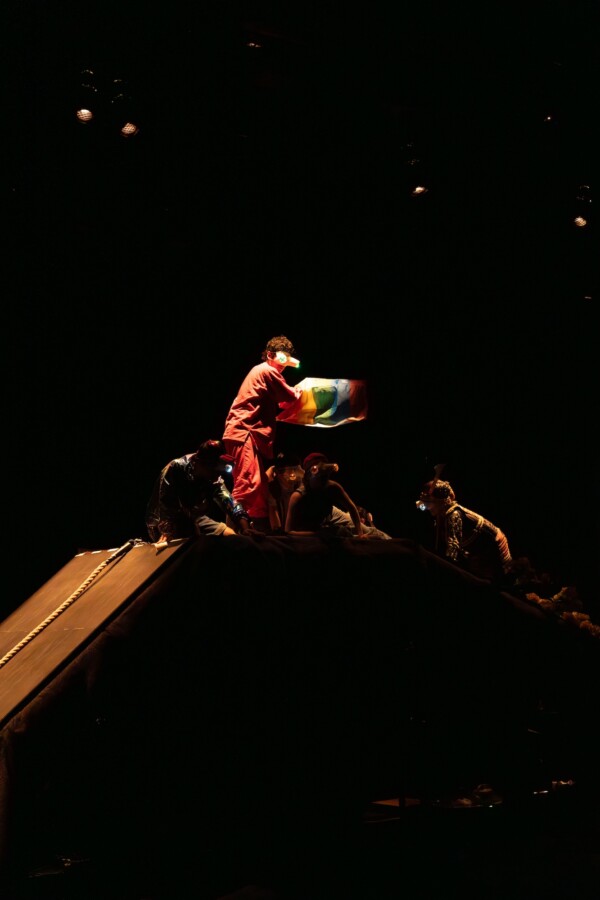

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

Jang-Chi

One of the reasons why we made games and deployed them like an installation is because we wanted to come to grips with the energy problem from a close range. Digital devices and liquid crystal are made from ores extracted from mines. A small quantity of rubbish (cache) accumulates just by using computers and smartphones. Even hives are constructed through the energy of bees. We made objects from beehives that had lost their utility for display, and in the game center, audience members can extract honey or vicariously experience a post-bee-human starting a demonstration on the street. In putting this play together, I consulted The Fable of the Bees, by Bernard Mandeville, a 17th-century Dutch physician and thinker. In this book, Mandeville discusses the nature of labor and the economy while using the beehive as a metaphor for society. Because he set forth the theory that personal greed drives society in an age when the term “capitalism” had not yet come into general use, the book reportedly created quite a stir. I nevertheless thought it was very contemporary.

Meguninja

My insertion of the demonstration scene was occasioned partly by seeing the demonstration demanding the impeachment of Yoon Suk-Yeol, Korea’s ex-president. Before I went, I thought I had checked out the situation fairly well on YouTube and other media, but things were pretty different on the site. The left-wing protestors were completely separated from the right-wing ones. The two sides held their demonstrations in different areas so that they could not directly confront each other. This made a strong impression on me. It was in contrast to the ceremony for laying flowers in memory of former prime minister Shinzo Abe in Japan. I saw this ceremony, and there was a confrontation between the left- and right-wingers there too, and the police intervened. Both sides, and those taking any position, presumably want to make the world better and life easier, but they end up opposing each other. It is quite a thorny problem. But when witnessed through a monitor or virtual space, the conflict seems to become milder or fuzzy to me. I don’t know whether things are going to get better or worse as a result.

Lin

To go back to the “eternal” in the title once more, although I am not sure you had this intention, I thought it might mean that existing in virtual space forever is one answer. To get an immortal body or live long would be hard to do in the material world, but could be done in the virtual one. Unlike the utopian visions of the past, it has become technically possible in the present. The choice of using VR at the end of the play could also be taken positively, as the space would allow eternal labor unfettered by real time and space.

Meguninja

There are several layers, but consider the influencer and video creator watching the demonstration in VR. Then there are the engineer and people crawling up from under the ground always seeking help from the start of the play, the story about Aso and the beekeeper repairing the roof, and the cram school teacher and Ji-Eun asking each other whether they like females or males. As the multi-layered conversation proceeds, the new world of VR overlaps on it. People can go back and forth between the VR world and the real world. The idea of VR arose as a way of hiding a real world that people do not want to see. I keenly realized something when I heard Lin’s remarks just now. I used the word “eternal” simply with reference to the situation of having to work forever and live with a purpose as long as you live. But In today’s world, we have two identities, one existing in the real world, and the other, in the virtual world. Our identity in human life disappears when our life is over, but that in virtual contents goes on existing. I noticed that “eternal” could be interpreted that way.

Aichi Triennale 2025 – Performing Arts category

OLTA, Eternal Labor

Photo: Yujiro Sagami

Courtesy of the Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee

OLTA

OLTA is an artist collective founded in 2009. Their work, ranging from agriculture to installations, explores the nature of collectives and identity in today’s world while reinterpreting the meaning of community, ceremony, folklore, historical events, and the specificity of land and space. Their fieldwork delves into marginalized communities within society as well as labor, history, and customs that are liable to be overlooked. Bringing together art and theatre, their performance work interweaves elements including text, art, people, space, light, sound, and video. The five members of OLTA –Inoue Toru, Saito Takafumi, Hasegawa Yoshiro, Meguninja, and Jang-Chi– have in recent years held many interdisciplinary performances at art festivals, theaters, and museums both inside and outside Japan. Through audience involvement, they create experiences that blur the lines between the present and the past, real and fiction, genders, and countries, all with a rebellious yet playful spirit.

Photo © Puzzle Leung. Courtesy of Vogue Taiwan.

River Lin

Working with Live Art and performance across the visual arts, theatre, and dance, River Lin is an artist and curator based in Paris and Taipei. His curatorial work advocates for cultural spaces and decolonial knowledge production that strengthen artist communities across local and international arts ecosystems. He works closely with queer, feminist, and Indigenous artists through dramaturgy, commissioning, and co-production.

Ongoing initiatives and curatorial projects include ADAM and Camping Asia (with Centre National de la Danse of France) by the Taipei Performing Arts Center, and the Indonesian Dance Festival. He has served as Curator of the 2023-2025 Taipei Arts Festival, Guest Curator of the 2025 Lyon Dance Biennial, and Co-Curator of 2022 BLEED by Arts House Melbourne.

Text: Keiko Kamijo

Photos: Ryuichiro Suzuki

Translation: